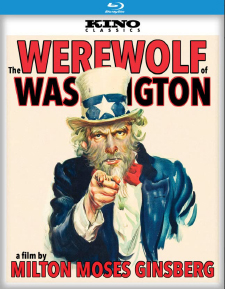

Werewolf of Washington, The (Blu-ray Review)

Director

Milton Moses GinsbergRelease Date(s)

1973 (February 21, 2023)Studio(s)

Diplomat (Kino Classics)- Film/Program Grade: D

- Video Grade: A-

- Audio Grade: A-

- Extras Grade: A-

Review

After watching The Werewolf of Washington (1973), digging into the extra features I was surprised by the fierce admiration expressed by critics and scholars for the film, its director’s cut, and reappraisal after half a century of almost total obscurity. Such passionate energies focused on such a forgotten picture is deeply commendable, though I was more than a little bemused by the degree of enthusiasm heaped on this oddball genre fusing.

Writer-director Milton Moses Ginsberg (1935-2021) was primarily an editor, particularly of award-winning documentaries. He directed just two narrative features: this one and, earlier, Coming Apart (1969), a divisive underground work made for just $60,000 starring Rip Torn and Sally Kirkland. Critics and audiences seemed to either love or hate it, though most admired Torn’s no-holds-barred performance, and the film was undeniably innovative.

For The Werewolf of Washington, Ginsberg attempts to combine the genre tropes of classic horror films, The Wolf Man (1942) particularly, while satirizing the destructive politics of the Nixon Administration, then in the throes of the Watergate scandal. Impressively, the movie was in theaters as early as February 1973, nearly 18 months before Nixon’s resignation, but the $100,000 production—incredibly cheap, even then—is a nearly unwatchable mess.

White House Press Secretary Jack Whittier (Dean Stockwell) is on assignment in Hungary when he’s bitten by a wolf that, once dead, turns out to be a dead gypsy—a werewolf. Upon his return to Washington, Jack begins turning into a werewolf himself under the full moon, committing a series of grisly murders, the victims all related to his work on behalf of the President (Biff McGuire). Jack agonizes over the realization of what’s happening to him, though his direct superior, Commander Salmon (Beeson Carroll, briefly Donald Penobscot on TV’s M*A*S*H) and others, including girlfriend Marion (Jane House), the President’s daughter, don’t believe him.

The werewolf scenes are mostly done straight and are pretty conventional, though there’s an almost-good scene involving Jack-in-werewolf-form terrorizing a woman trapped in an overturned pay phone booth, and Stockwell, apparently never doubled by someone else, is impressively energetic and sometimes humorous (with dog-like reactions, occasionally) in the not-bad makeup. Generally, though, this material feels completely detached from Ginsberg’s political aims, and lacks the jet-black humor found later in movies like An American Werewolf in London. The intended satirical political aspects of the film really don’t work on any level. There’s no effort to integrate the horror aspects with the political satire, while the writing of the primarily political scenes mostly consists of characters expressing right-wing conservative talking points of the day: anticommunism bordering on hysteria, blatant racism, anti-press and free speech, gung-ho pro-Vietnam War militarism, etc. In Ginsberg’s script, all the failings of the Nixon years are expressed by various characters, but he really doesn’t do anything with them beyond pointing out how ridiculous and fanatical these policies sound, spoken aloud.

Reportedly Ginsberg kept revising the script and reshot scenes to keep pace with the ever-changing revelations involving Watergate but, curiously, the film feels much more disconnected from that scandal than one might have expected. For one thing, actor Biff McGuire looks nothing like Nixon and comes off more like a doddering Ronald Reagan; missing entirely is the paranoia and mental deterioration captured so perfectly by actor Philip Baker Hall and director Robert Altman later with Secret Honor (1984). The low budget hurts, too: despite some good material of Stockwell on location in Washington, D.C., interior scenes try recreating executive-level meetings and press briefings in what look like motel suites inadequately doubling for Pentagon and White House conference rooms; these fail to convince. Other scenes are damaged by amateurish camerawork and editing: a restaurant conversation between Jack and Salmon is seriously marred by cutting between two almost identical camera angles each oddly framing the two actors (or cutting one out entirely) giving the scene an unintended surrealist quality.

The Werewolf of Washington was barely released when it was new, disappeared entirely for many years, then began turning up on home video from bargain labels wrongly assuming the film was in the public domain, and which used terrible video masters. Kino Lorber’s new 2K video transfer of the original theatrical version (89:27) is presented in 1.85:1 widescreen and looks great, as well it should since it’s doubtful more than five or six prints were ever struck. The Region-Free disc actually defaults to Ginsberg’s 74-minute director’s recut, completed the year of Ginsberg’s death. (Press releases touted a 4K restoration of the director’s cut, but this isn’t mentioned anywhere on the packaging, and looks identical, picture-wise, to the theatrical version.) The director, contractually obligated to deliver a near-90-minute feature, wisely cut some of the fat for this version, and changed all the Hungary scenes from color to black-and-white, along with some other minor changes to the musical score, etc. The short version plays a little better, but it can’t undo the picture’s fundamental problems. Both cuts are in good LPCM 2.0 mono and come with optional English subtitles.

Supplements include an 8:27 interview-by-Zoom interview with Ginsberg, conducted by Jacob Perlin, who apparently spearheaded the restoration; a critical analysis (also via Zoom) by Roger Ebert-dot-com writers Simon Abrams and Sheila O’Malley (18:53); a theatrical trailer (2:21) and TV spot (:26). Also included is a trailer for Coming Apart. Much as I disliked the film, it was heartwarming to see the ailing Ginsberg so pleased by the grassroots efforts to resurrect both features, and the enthusiasm expressed by Abrams and O’Malley, even if I can’t share in their passion.

- Stuart Galbraith IV