Storm Center (Blu-ray Review)

Director

Daniel TaradashRelease Date(s)

1956 (August 18, 2025)Studio(s)

Phoenix Productions/Columbia Pictures (Indicator/Powerhouse Films)- Film/Program Grade: B

- Video Grade: A-

- Audio Grade: A

- Extras Grade: A-

Review

[Editor’s Note: This is a Region B-locked British Blu-ray import.]

Storm Center (1956) is notable as the first mainstream Hollywood feature to openly criticize anticommunist hysteria, red-baiting, and censorship. That alone makes it interesting, and its screenplay raises a number of interesting observations about those dark times, but the picture is also extraordinarily clunky dramatically, even unreal, and unevenly acted and directed. This was the only directorial credit for screenwriter Daniel Taradash, whose writing credits include Golden Boy (1939), Rancho Notorious, Don’t Bother to Knock (both 1952), From Here to Eternity (1953), Picnic (1955), Bell, Book and Candle (1958), and Hawaii (1966). Many of these were adaptations, and the resulting films are variable, but he was definitely above average as a writer.

The screenplay, by Taradash and Elick Moll has both good and bad dialogue, but the larger problem is Taradash’s direction: some scenes are very awkwardly staged, and the script partly pivots around a young boy, a central character in a relationship critical to the story. The child actor playing the boy is not good, but he’s not helped by Taradash’s seemingly non-existent direction of any of the actors, nor by his terrible dialogue in those scenes with the child particularly.

Suggested by a real-life case involving librarian Ruth W. Brown of Bartlesville, Oklahoma, Storm Center stars Bette Davis as Alicia Hull, a widowed, politically liberal small-town librarian beloved by the children who come to borrow books and who develop a love of reading under her guidance, especially ravenous reader Freddy Slater (Kevin Coughlin). She is surprised when the city council invites her to lunch and quickly votes to approve her long-held dream to add a children’s wing to the library.

But this turns out to be an unsubtle bribe: aspiring politician Paul Duncan (Brian Keith) wants Hull to remove one book from circulation, The Communist Dream. Duncan tries threatening her by noting her past associations with left-wing organizations, several later exposed as “communist fronts.” Nevertheless, principled Hull refuses to pull the book prompting even lifelong friend Judge Robert Ellerbe (Paul Kelly) to reluctantly join those unanimously voting to fire her. Further, she is ostracized by most of the community and, worse, by even the children, including Freddy, whose philistine father (Joe Mantell) and others push the conflicted lad into thinking she’s some kind of red menace, resulting in his having a mental breakdown.

The film has undeniably good intentions, some of which peer through and reveal what might have been a great, landmark film. One scene of books burning is stylistically similar to that found in François Truffaut’s later, much superior Fahrenheit 451. Another good scene, though heavily compromised by Taradash’s staging, with Davis seated on the far-right end of a long table, her adversaries improbably all seated on one side of the table, facing the camera, has Hull explaining that her library has had a copy of Mein Kampf on its shelves for decades without anyone complaining. She agrees The Communist Dream is rubbish propaganda, but persuasively argues that, like Hitler’s book, The Communist Dream should be made available so that patrons can read it for themselves and draw their own conclusions.

Unfortunately, all of the scenes involving child actor Kevin Coughlin—who went on to become a decent adult actor, mostly on television, prior to his untimely death in a hit-and-run accident at age 29—are painfully phony. Coughlin’s not up to the task, Taradash is of no help, and the writing lacks any credibility. His scenes with Davis and Mantell are laughably unreal and forced. Further, while Davis’s performance is itself fine, even excellent in conveying Hull’s frank assertiveness, she also lacks the kind of grandmotherly warmth the part desperately needed to validate Freddy’s total devotion and subsequent heartbreak. Davis’s costuming and makeup don’t help: she looks like a stereotypical frumpy librarian. Perhaps someone like Spring Byington, a character actress positively beloved at the time, would have been better suited and more credible than Davis in old-age makeup and tweed suits.

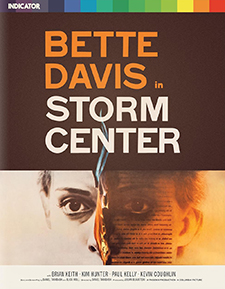

Probably made inexpensively for either side of $1 million, Storm Center nevertheless exudes sincerity. Initially conceived as a project for liberal producer Stanley Kramer to have starred Mary Pickford and, later Barbara Stanwyck (surprising given that both actresses were politically quite conservative), the film still retains a singular lefty air: Kim Hunter, then gray-listed, has a thankless part as Brian Keith’s girlfriend, but she was probably drawn to the film’s message. Likewise, the Saul Bass poster art and title design remind viewers of his association with another ‘50s liberal filmmaker, Otto Preminger.

One guesses the reason Columbia made the film at all was to a) keep Taradash happy, as he was the studio’s most important screenwriters of the period (From Here to Eternity may have been their biggest hit until Bridge on the River Kwai); and, b) lowly Columbia was able to acquire the services of Bette Davis, then on a career slide between All About Eve and Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? a dozen years later, but still a major star. It’s just too bad Storm Center is all-thumbs.

A Region “B” locked Blu-ray from Powerhouse Films/Indicator, Storm Center is presented in its original black-and-white, 1.85:1 widescreen, billed as a recent remastering. Possibly because so much of the picture was shot on location (Santa Rosa, California) or maybe Columbia was just being cheap, like other lesser Columbia titles the film is notably grainy, as if the filmmakers used a higher-speed film to reduce the need for complex lighting set-ups. Whatever the case, this is a good presentation approximating the original theatrical release. The original LPCM 2.0 mono is supported by optional English subtitles. This is billed as a limited edition restricted to 3,000 copies.

Supplements consist of a new audio commentary by Jason A. Ney; Lies Lanckman on Storm Center, a featurette about the film’s themes and production; an audio-only interview with Saul Bass from 1986; a trailer and image gallery of publicity material.

Unfortunately, were only sent a check disc and not the final release, which contains and booklet and additional material, so we cannot cover it.

As a historical document, Storm Center is a must-see. One can forgive its dramatic clumsiness to a point, but at times it really does serious damage to the film. Still, recommended.

- Stuart Galbraith IV