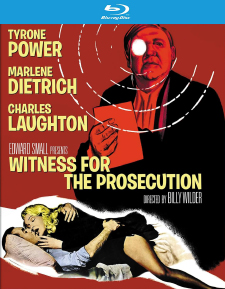

Witness for the Prosecution (Blu-ray Review)

Director

Billy WilderRelease Date(s)

1957 (February 6, 2024)Studio(s)

United Artists (Kino Lorber Studio Classics)- Film/Program Grade: A-

- Video Grade: A

- Audio Grade: A

- Extras Grade: A

Review

Agatha Christie’s novels and short stories have provided source material for countless movies, among the more famous And Then There Were None, Murder on the Orient Express, Death on the Nile, and Evil Under the Sun. Witness for the Prosecution is firmly in this category. Based on Christie’s 1953 stage play, the film commands our attention with intriguing characters and more than a few plot twists in a courtroom drama that keeps us guessing.

London barrister Sir Wilfrid Robarts (Charles Laughton, The Hunchback of Notre Dame) has just been released from the hospital following treatment for a major heart attack. Under doctors’ orders, he grudgingly tolerates round-the-clock care of a private nurse, Miss Plimsoll (Elsa Lanchester, The Bride of Frankenstein), whose insistence that he avoid stress and cigars and take his medicine and his naps irritate him no end.

Sir Wilfrid’s doctors also advised that he cut down on his practice and take no major cases. Miss Plimsoll tries her best to make sure of that, but when a solicitor colleague (Henry Daniell, Lust for Life) arrives with an urgent case—and a couple of cigars in his pocket—Sir Wilfrid locks the nurse out of his study, ostensibly to hear him out but mostly to indulge in a forbidden smoke.

The case is a difficult one. Amateur inventor Leonard Vole (Tyrone Power, The Sun Also Rises) is the prime suspect in the murder of a wealthy widow. He has often been seen in her company and the police have discovered that her newly revised will names him as the major beneficiary. All the circumstantial evidence points to Vole as the killer. Nevertheless, having questioned Vole minutely, Sir Wilfred believes he’s innocent and agrees to take the case. Shortly afterwards, Vole is arrested on suspicion of murder.

Vole’s sole alibi is his wife, Christine (Marlene Dietrich, Destry Rides Again). The defense becomes even more complicated when Christine shows up at Sir Wilfrid’s and coldly, without a trace of emotion at her husband’s plight, agrees to testify on his behalf. As the trial progresses, Sir Wilfred must keep Miss Plimsoll at bay as he confronts an increasingly daunting series of unforeseen revelations.

Director Billy Wilder, working with a screenplay by himself and Harry Kunitz, has fashioned a riveting drama with lots of humorous touches, notably the repartee between fussy Miss Primsoll and sardonic Sir Wilfred. The dialogue is sharp and witty, the plot layered like an onion with bits of information that constantly change the outlook of the trial.

Performances are uniformly outstanding, beginning with Laughton, whose cantankerous Sir Wilfred risks his health to take on Vole’s case. Laughton’s mannerisms, speech patterns, and body language are all in full force. He’s seldom off screen and clearly dominates every scene he’s in. His Sir Wilfrid phrases his interrogations and objections with eloquence and a hint of condescension, shutting down many of the prosecutor’s questions and witnesses. Railing against being nagged to down a pill, drink his cocoa, or take a nap, he manages to find ways to foil his “keeper,” the omnipresent Miss Plimsoll (Laughton and Lanchester were married at the time). The role is tailor-made for Laughton.

Lanchester’s Miss Plimsoll is reminiscent of Miss Preen in The Man Who Came to Dinner—a perfect comic foil. She’s an annoying thorn in Sir Wilfrid’s side and makes for some bright, colorful, humorous give-and-take as two strong-willed individuals clash.

Power, usually cast as a romantic lead or action hero, doesn’t have the biggest role despite having the greatest star power. His role often requires reacting silently to a series of witnesses as his Vole stands in the courtroom’s dock. In his one big scene, when Vole shouts out as a witness incriminates him, he overplays to the rafters, savoring his only Big Moment. Vole is seen in flashbacks befriending the murder victim, elderly Mrs. French (Norma Varden, Strangers on a Train), and he’s both kindly and complimentary towards her.

Dietrich plays the enigmatic Christine Vole, whose motivations are never quite clear. Christine is herself a mystery in terms of her choices to provide the alibi that will possibly exonerate her husband. Projecting an icy personality, Dietrich epitomizes self-assurance, independence, and intelligence.

Una O’Connor (The Invisible Man), who portrays Mrs. French’s housekeeper, has a wonderful scene on the witness stand. Nervous and unaccustomed to the formality of a courtroom, she fidgets, pushes away a microphone, and conveys the feeling that she’s being inconvenienced. Struggling to hear the lawyers, she’s a model of working-class indignation.

The supporting cast in composed of excellent veteran actors, including John Williams (Dial M for Murder), Torin Thatcher (The Robe), Ian Wolfe (The Silver Chalice), Francis Compton (Rage in Heaven), and Philip Tonge (Hans Christian Andersen).

Witness for the Prosecution was nominated for six Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor (Laughton), and Best Supporting Actress (Lanchester). Lanchester won a Golden Globe for her performance.

Witness for the Prosecution was shot by director of photography Russell Harlan on 35 mm black & white film with spherical lenses and presented in the aspect ratio of 1.66:1. Kino Lorber Studio Classics re-issues the film on Blu-ray with the same transfer as their 2014 Blu-ray release, but now encoded at a higher bitrate on a BD-50 disc. Clarity and contrast are excellent, making the film practically sparkle. Details are well delineated, such as items on Sir Wilfrid’s desk, his barrister wig, patterns in clothing, perspiration on Laughton’s plump face, and bulging eyes and deep wrinkles on O’Connor’s face. Blacks are deep and velvety and the grayscale nicely rendered. Rear projection is used in a scene shot from inside a car as Sir Wilfred and nurse Plimsoll make their way to Sir Wilfrid’s residence. The monochromatic photography gives the film an austere quality. The mid- 1950s was an era in which more serious, dramatic subjects were shot in black & white, with color mostly used for musicals, outdoor adventure films and comedies.

The soundtrack is English 2.0 mono DTS-HD Master Audio. Newly-included English SDH subtitles are an available option. Dialogue is clear and distinct. A number of accents can be heard, including Power’s standard American, Laughton’s upper-class educated British, and O’Connor’s Irish. There’s occasional rumbling in the courtroom. Dietrich, in a flashback, sings the song I May Never Go Home Anymore as she ambles among a rowdy crowd whose alcohol-soaked enthusiasm leads to a melee.

Bonus materials on the Region A Blu-ray release from Kino Lorber Studio Classics (which also features a new slipcase) include the following:

- Audio Commentary by Joseph McBride

- Billy Wilder and Volker Schlondorff Discuss Witness for the Prosecution (6:31)

- Trailer (3:08)

- Five Graves to Cairo Trailer (2:13)

- The Lost Weekend Trailer (2:08)

- A Foreign Affair Trailer (1:01)

- Stalag 17 Trailer (2:08)

- Some Like It Hot Trailer (2:23)

- The Apartment Trailer (2:20)

- One, Two, Three Trailer (2:11)

- Irma La Douce Trailer (3:53)

- The Fortune Cookie Trailer (2:37)

- The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes Trailer (3:01)

- Avanti Trailer (2:39)

- The Front Page Trailer (2:37)

Audio Commentary – Joseph McBride, author of Billy Wilder: Dancing on the Edge, refers to Wilder as one of the most versatile directors. Witness for the Prosecution was adapted from the 1925 short story Traitor’s Hands, published in 1933 as The Witness for the Prosecution in a collection called The Hound of Death. The play adaptation was first performed in London in 1953 and was a hit on Broadway in 1954. The story was produced often for television, most notably in a 1982 version based on the original Wilder screenplay and starring Ralph Richardson in Laughton’s role, Deborah Kerr as the nurse, Beau Bridges as the accused Leonard Vole and Diana Ring as his wife Christine. Wilder made Witness for the Prosecution right before Some Like It Hot. He was “running for cover” during the 1950s because of the negative reaction in the U.S. to his Ace in the Hole (1951), a dark view of what a reporter will do to keep a story alive. He turned to “safe” projects, such as adaptations of stage plays and comedies. With Love in the Afternoon, Wilder began a long-time collaboration with I.A.L. Diamond. Before Tyrone Power was cast, other actors were considered for the role of Vole—Jack Lemmon, Gene Kelly, Roger Moore, and Kirk Douglas. Power’s film career was waning in 1957 and he was too old and too American for the part. Witness for the Prosecution was Power’s last completed film. He died in 1958 on the set of Solomon and Sheba at age 44. As an actor, Charles Laughton achieved success very quickly in London and was in demand for big roles on the stage and subsequently in movies. Laughton directed only one film, The Night of the Hunter, which was a box office failure but considered a classic now. Marlene Dietrich was brought to Hollywood by Josef von Sternberg, who directed her in several films, making her a star. During World War II, she went to Europe to entertain American troops on the front lines. For years after the war, she was resented by the German people. In the 1950s, as her movie career faded, she developed a successful nightclub act. According to those who knew her well, Dietrich was a regular “hausfrau” who loved to cook and clean. Una O’Connor is the only person in the film cast to re-create her stage role, as the housekeeper. A concise overview of Billy Wilder’s career in Europe and America is provided. Wilder and co-writer Harry Kurnitz outdo Agatha Christie. Sir Wilfrid’s heart condition, the fussy nurse, and the ending are all inventions of the film. Wilder and other directors resented studio censorship at the time but came to realize that it made their pictures more clever in how subjects were portrayed. Wilder noted that making Witness for the Prosecution was one of his happiest experiences as a director.

Billy Wilder and Volker Schlondorff – Conducted mostly in German (with English subtitles), this interview has Wilder complimenting Agatha Christie on “very good plotting.” He contends that her weakness is flat writing. The construction of dialogue—not the writing of it—is the toughest job, but the audience must not be aware of the construction. Facing two options, the main character should make the noble choice. Marlene Dietrich brought the project to Wilder, indicating she’d do the film only if Wilder directed. Speaking about his star, Wilder says “Laughton was dynamite.” Art director Alexandre Trauner created the train station set in a small studio and the Old Bailey set, which is almost a character in itself.

Opening up a stage play for film is always tricky. The director wants to retain the dramatic essence of the work while keeping it visually interesting. Director Wilder succeeds on both counts. With a strong cast, a brisk pace, and surprises turning up periodically, he maintains tension and keeps us guessing. With liberal doses of witty banter, Witness for the Prosecution is smart, suspenseful, and captivating. The final scene, a product of the Production Code, may tie things up a little too neatly, but the film is otherwise a delight.

- Dennis Seuling