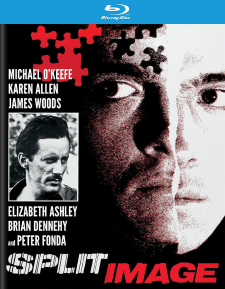

Split Image (Blu-ray Review)

Director

Ted KotcheffRelease Date(s)

1982 (January 9, 2024)Studio(s)

PolyGram Pictures/Orion Pictures (Kino Lorber Studio Classics)- Film/Program Grade: B

- Video Grade: A

- Audio Grade: A

- Extras Grade: B

Review

Some films not promoted as horror films often are genuinely terrifying because they center on distressing events that actually could happen and have occurred. Split Image is one of these pictures, a tale of indoctrination and a family’s attempt to rescue their brainwashed son from a cult-like commune.

Danny Stetson (Michael O’Keefe, The Great Santini) is a bright, good-looking high school student and star gymnast from an affluent suburban home. When we first see him, he’s practicing so hard on the high bar that his hands are bleeding, yet he goes back and pushes himself to continue. At a bar, he’s attracted to Rebecca (Karen Allen, Raiders of the Lost Ark). They hit it off and she invites him to the “community center” where she works to watch a screening of the film Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. After the film, the members have a lively discussion about the duality of human nature. Soon after, they head for a place called Homeland, a religious community of young people presided over by their charismatic leader, Neil Kirklander (Peter Fonda, Ulee’s Gold).

The recruits to Homeland are always surrounded, never allowed any privacy, deprived of food and sleep, told to avoid sexual contacts, and encouraged to confess their insecurities in group sessions. Initially skeptical, Danny finally breaks down and joins the group. He’s given a ceremonial haircut and a new name—Joshua. Rebecca, it’s revealed, was originally Amy.

Alarmed by their son’s sudden change of behavior and failure to return home, Danny’s parents, Kevin (Brian Dennehy, Cocoon) and Diana (Elizabeth Ashley, The Carpetbaggers), visit Homeland, where they’re stonewalled by Kirklander and told by Danny himself that he has found a new home.

The parents subsequently receive a visit from Charles Pratt (James Woods, Videodrome), an expert at retrieving kids from cults and de-programming them. He explains that because Danny’s no longer a minor, his parents could face kidnapping charges if the de-progamming is unsuccessful. Desperate, they hire him anyway. Pratt and his team eventually grab Danny when he’s been assigned by Kirklander to solicit money in public for a phony charity. They strong-arm him back to his parents’ home, where a room has been prepared for his de-programming.

O’Keefe is convincing as both the popular Danny who appears to have a charmed life and the robotic Joshua he later becomes. He really has a dramatic challenge during the de-programming sequences. Sweating, terrified, and violent, his Danny is like a caged wild animal, requiring several men to constrain him. Windows are boarded, doors are locked, and for a short time, he’s handcuffed. Several close-ups in these scenes show Danny’s terror dissipate as Pratt’s techniques make inroads into Danny’s clouded mind.

Woods has a field day as Pratt, a no-nonsense warrior who’s parents’ last resort in reclaiming their lost children. Loud, foul-mouthed, and arrogant, he nonetheless knows the job of de-programming isn’t quick or easy and in it for the long haul. The parents are of secondary concern to Pratt, and he asks for their help only when they may aid Danny’s outcome. Woods’ performance, intense and always at a feverish pace, enhances the film’s tension.

As the concerned parents, Dennehy and Ashley appear too calm throughout Danny’s ordeal. Yes, they’re concerned, but there’s a coolness that fails to ring true since so much is at stake. We don’t need histrionics, but greater emotional expression would have given them greater relatability. The problem is likely the screenplay, which relegates them to minor characters in the film’s final third.

Fonda plays Kirklander as a reassuring presence who’s expert at taking advantage of young people’s loneliness, alienation, and insecurities. His “love” for the cult members is false, his motives selfish, and his power the weapon with which he breaks down young minds through carefully sequenced activities. And he knows that the law protects him against parents’ attempts to get their kids back, provided that the kids are no longer minors. As soon as they turn 18, they’re adults in the eyes of the law and their parents no longer have any legal say about their choices.

The major question I had with Split Image is why Danny is drawn to the cult in the first place? The early part of the film depicts him as happy. There are no hints that he resents his family, his school, or his friends. His instincts are to find the activities and residents of Homeland odd, but he soon succumbs. He seems so well adjusted that making him this readily fall in step with the cult lifestyle is perplexing. The script uses his attraction to a girl as the carrot, but is that enough to make him a convert to a way of life utterly at odds with all he has known and loved?

The feel of Homeland is familial and harmonious, with sing-alongs community dining, and general camaraderie integral to daily life. On the surface, this is a Utopia with cares and worries left in the outer world. Director Kotcheff gradually reveals the insidiousness of the cult and its methods to mold young people into human puppets.

Production design is lavish, with an entire community created in a vast area with numerous structures, a vegetable garden, barracks-style sleeping quarters, workshops, ongoing construction, and ceremonial areas. Obviously, great care went into the design of the compound, and its remoteness is a major way of isolating its young people from outside influences.

Split Image was shot by director of photography Robert Jessup on 35 mm film with Panavision cameras and lenses and presented in the aspect ratio of 2.39:1. The Blu-ray, sourced from a 2K scan of the 35 mm interpositive, features a 2.35:1 aspect ratio. Stability is excellent. There are no visual imperfections—no scratches, dirt specks, clouding, or cue marks. Clarity is sharp and details nicely delineated, particularly decor in the Stetson home, clothing, leaves on trees, and markings on a police car. Complexions are natural, with sweat on Danny’s face during his de-programming prominent. There are intentional picture distortions from Danny’s point of view during his de-programming. Karen Allen’s freckles are visible in her close-ups. The color palette is broad, from vibrant greens in the trees, grass, and bushes at the Homeland complex to more muted tones in the “uniforms” the Homeland members wear when they solicit money on streets.

The soundtrack is English 2.0 DTS-HD Master Audio. Optional English SDH subtitles are available. Dialogue is clear and distinct. There are raised voices from Woods and O’Keefe during the de-programming scenes, community singing of folk songs, a police car siren, physical tussles, and fight noises. Bill Conti’s music contributes to the film’s moods, with a hint of Rocky-style music as Danny practices on the high bar.

Bonus features on the Region A Blu-ray release from Kino Lorber include the following:

- Audio Commentary by Film Historian/Filmmaker Daniel Kremer

- Trailer (2:39)

- Gorky Park Trailer (2:24)

- 52 Pick-Up Trailer (1:45)

- The Bedroom Window Trailer (1:59)

- The Wanderers Trailer (1:53)

- The Hard Way Trailer (2:04)

Audio Commentary – Ted Kotcheff is a Canadian director whose films include North Dallas Forty, Fun With Dick and Jane, and Weekend at Bernie’s. Commentator Kremer made a film himself about de-programmers and spoke to people who had been de-programmed. He was inspired by the Jim Jones cult’s mass suicide in Guyana. Other notable films that deal with cults include Ticket to Heaven and Blinded By the Light. A familiar theme of director Kotcheff involves social climbers. Split Image is very much a “Reaganist era” picture about a well-off character who wants more than what he has. He looks up to the spiritual to fill a void in his life. This release of Split Image is the first time the film has been seen in widescreen on home video, and several shots illustrate how adept Kotcheff is at composing for a wide screen. This is one of only a few widescreen films Kotcheff made. The subject matter was relevant to the 1980s. Polygram was the company behind the film, part of a multi-picture deal. Michael O’Keefe worked for ten weeks with a gymnastics trainer and performed most of the movements in the first scene of the film. Brief career overviews are provided for Karen Allen, Brian Dennehy, and Elizabeth Ashley. Production designer Wolf Kroeger planned and executed the physical look of Homeland, which was filmed at a defunct 400-acre animal park in Texas. Several structures, including geodesic domes, windmills, and a pyramid-shaped building, were constructed. Several advisors contributed their input about de-programming. Once de-programming ends, the psychodrama continues because the question of privilege figures in. Why did a person from a “cushy life” escape?

Split Image is a well made film that portrays the methods used by cults to lure and retain members. By focusing on a single individual, the story becomes very personal, as we root for Danny to escape the clutches of Kirklander and Homeland. It’s hard not to think of the Jonestown Massacre as we see an idealistic commune function far from the eyes of outsiders. The film graphically shows the visceral, raw rigors of de-programming and the sacrifices a family must endure to have their child returned to them.

- Dennis Seuling