Long Voyage Home, The (Blu-ray Review)

Director

John FordRelease Date(s)

1940 (May 31, 2023)Studio(s)

Argosy Pictures/Walter Wanger Productions/United Artists (Imprint/Via Vision)- Film/Program Grade: A

- Video Grade: A

- Audio Grade: A-

- Extras Grade: A-

Review

During 1939-41, John Ford had an incredible run directing some of the best American films of all-time: Stagecoach, Young Mr. Lincoln, and Drums Along the Mohawk in 1939, The Grapes of Wrath and The Long Voyage Home in 1940. He was no slouch in 1941, either, with How Green Was My Valley; Tobacco Road was his only disappointment.

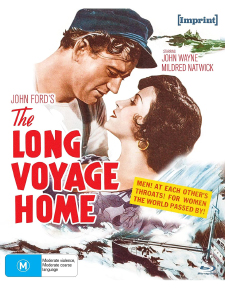

Among these, The Long Voyage Home was Ford’s most unusual, an experimental adaptation by Dudley Nichols of four plays by Eugene O’Neill. The playwright so loved the film he reportedly wore out a print given him by Ford. Instead of the rowdy seafaring adventure film promised on the film’s posters, audiences were gut-punched by a wrenching story of doomed men aboard a tramp steamer in the early days of the war, when every crossing of the Atlantic was fraught with peril. Moodily shot in stark black-and-white by Gregg Toland, it was an ensemble piece with no single protagonist, and little in the way of story. John Wayne, still years away from true stardom outside of B-Westerns, gets top billing, but even Ford regular John Qualen has a bigger part.

The SS Glencairn is en route from the West Indies to England, stopping briefly in the States to load a cargo of dangerous high explosives for the war effort. Though their captain (Wilfred Lawson) is a fair man, the men look to garrulous Irishman Driscoll (Thomas Mitchell) as their leader. Also aboard is Smitty (Ian Hunter), a brooding alcoholic Englishman, clearly fallen from Britain’s elite class; Ole Olsen (John Wayne), a Swede ten years at sea everyone is determined to see safely home to his mother; Yank (Ward Bond), a hard-drinking, lascivious hand always looking for a good time but terrified when faced with his own mortality; Donkeyman (Arthur Shields), an introspective Irishman watching over the suicidal Smitty; bellyaching steward Cocky (Barry Fitzgerald, Shields’s real-life brother); and Axel (Qualen), who looks after fellow Swede Ole like a mother hen.

The 105-minute film has little in the way of story; rather, it’s a mood piece, dripping with atmosphere and stylized, poetic dialogue. During a fierce storm one of the men is fatally injured with a punctured lung; with no doctor aboard, the captain and crew can do little but watch him slowly, painfully die. Smitty’s suspicious behavior makes some concerned that he might be a German spy, endangering all aboard. A German plane threatens the ship, dropping bombs and strafing the deck with machine gun fire. In London, everyone is excited to see Ole off on the final leg of his passage, but an agent (J.M. Kerrigan) for a veritable slave ship looking to shanghai a crew sets his sights on Ole, aided by an accomplice, prostitute and alcoholic Freda (Mildred Natwick, in her film debut), who clearly wants no part of the dirty deed.

Ford directed his actors with great care and an eye on every detail. None of the performances is less than very good, and all the men could pass as real, hardened sailors. Only Thomas Mitchell is very slightly disappointing when one becomes aware Ford had wanted another of his regulars, Victor McLaglen, for the part. McLaglen asked for too much money, so Mitchell got the part. Mitchell is fine, but it’s easy to imagine McLaglen playing it just as broadly but less theatrically fine-tuned, and more genuinely heartfelt.

Wayne was a better, more hardworking actor than many realize. Osa Massen (Rocketship X-M) coached Wayne on his Swedish accent, and he comes off well. Probably the best performances in the film are from Arthur Shields, whose character is resigned to his fate and who mostly observes the others; and Natwick, who projects myriad conflicting emotions in a relatively small part, confined to the last 10 minutes or so of the picture.

When Orson Welles saw The Long Voyage Home, he knew he wanted Gregg Toland to shoot Citizen Kane. Indeed, Welles likewise so respected his artistry he copied the unprecedented screen credit Ford gave Toland: Ford as Director and Toland as Director of Photography share the same title card.

Toland deserved it. Inky-black and high contrast shadows, deep-focus photography (aided here, as in Kane, by rear-projection process shots, which Toland uses almost like mattes), characters moving in and out of light, distorted close-up, low and visible ceilings with much lighting from floor-level, and striking compositions in which action moves toward and away from the camera. His innovative techniques helped invent film noir and inspired later cinematographers like John Alton.

Imprint’s Region-Free disc boasts a stunning video transfer (1.37:1 standard ratio, in its original black-and-white) culled from a 2016 UCLA Film & Television Archive restoration. The image is impressively sharp with essential inky blacks. The LPCM 2.0 mono, English only with optional English subtitles, is also excellent.

Bountiful supplements include a new audio commentary by film historians Alain Silver and Jim Ursini; a new video interview (26:22) with film professor José Arroyo; a new interview with Cambridge University English professor Jean Chothia about adaptations of O’Neill (28:19); and a previously released video essay (16:41) by Tag Gallagher, the other of John Ford: The Man and His Films. All three incorporate footage from the film, and Gallagher’s video essay includes images of all the paintings commissioned by great 20th century artists to promote the film.

As Arroyo points out, The Long Voyage Home is rather unaccountably underrated by film historians even though, clearly, it’s one of the best films by one of the greatest filmmakers of all-time. Imprint’s release does it justice, and a must-own.

- Stuart Galbraith IV