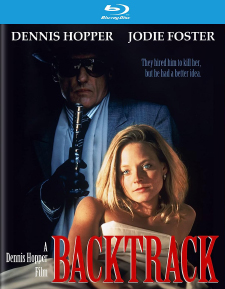

Backtrack (aka Catchfire) (Blu-ray Review)

Director

Dennis HopperRelease Date(s)

1990 (April 25, 2023)Studio(s)

Dick Clark Productions/Vestron Pictures (Kino Lorber Studio Classics)- Film/Program Grade: B-

- Video Grade: A-

- Audio Grade: B+

- Extras Grade: B

Review

Backtrack (1990), also known as Catchfire and directed by actor Dennis Hopper, is not exactly a good film but, by golly, it sure is an interesting one. Co-starring Jodie Foster immediately prior to Silence of the Lambs, Backtrack is a strange neo-noir romantic thriller, far more coherent than Hopper’s notorious The Last Movie but with similar tangential preoccupations with quirky characters, indulgent actorly moments, and occasionally interesting visual stylization. For its wildly diverse supporting cast alone, some appearing without screen credit, the movie is worth a look.

Produced by the theatrical features arm of Dick Clark Productions and originally released by Vestron Pictures (bankrupt soon after), the film was in trouble from the get-go: script problems complicated by the long 1988 Writers Guild strike, Hopper and Foster famously feuding during production, and reportedly Hopper’s first cut ran upwards of three hours. Hopper disowned the 100-minute theatrical version, re-edited by others, and shortly after prepared his own 116-minute “director’s cut.” Both versions are on Kino’s new Blu-ray, both bearing the Backtrack title, albeit with different opening title designs.

Anne Benton (Foster) is a conceptual artist, specializing in LED signs flashing little homilies. Driving home one night, her vintage Mustang gets a blowout on the freeway and, seeking assistance, she wanders off into an industrial area where she witnesses mafioso Leo Carelli (Joe Pesci) slitting another gangster’s throat. Seeing her flee the scene, Carelli sends torpedoes Pinella (John Turturo) and Greek (Tony Sirico) after her, but they only succeed in shooting Anne’s boyfriend, Bob (Charlie Sheen).

FBI agent Pauling (Fred Ward) offers to put Anne into a witness protection program, but at his offices she spots Corelli’s laconic lawyer, John Luponi (Dean Stockwell), also present at the murder, so in a panic Anne hightails it to Seattle, working at an advertising copywriter under an assumed name. Mob boss Lino Avoca (Vincent Price) hires top hitman Milo (Hopper) to track her down.

Moving again to New Mexico, Anne reestablishes herself at a theater-cum-art performance space managed by a former art teacher (Julie Adams) but Milo easily tracks Anne down once again. By this time, however, Milo has fallen in love with his intended hit and, improbably, she soon becomes fascinated with him.

Though highly watchable for its cast and general strangeness, Backtrack has many obvious major problems. Key among them is Hopper’s own performance, which he unconsciously plays like a very bad imitation of Jack Nicholson’s inarticulate New York hitman in John Huston’s Prizzi’s Honor (1985). Hopper’s Brooklynese comes and goes, and his dopey way of communicating contradicts what director Hopper shows us about the character, who uses a sophisticated computer system to track Anne’s movements, and whose tastes run to jazz and artists like Hieronymus Bosch. The screenplay never comes anywhere close to adequately explaining why Milo is attracted to her, let alone she to him. Foster comes off somewhat better, despite the singularly ugly costume design given her character, and a gratuitous, awkwardly lingering nude shower scene, by all accounts an act of revenge by Hopper against Foster.

Hopper’s direction obsesses over odd details straining credibility, particularly, strangely enough, the set decoration. Milo’s improbably lavish HQ, paid for by the mob, unhesitatingly spares no expense on what would seem a straightforward, even ordinary contract killing. Anne leaves town with but the clothes on her back, yet wherever she relocates, she seems to have no difficulty obtaining bulky pieces of her LED art to decorate her latest hideout. Likewise, Hopper’s camera is drawn to Last Movie-like Native American ceremonies and other colorful but irrelevant matters, including, in an amusingly coincidence, a sequence in which Foster’s character rescues a lamb.

Despite the size of his role, Joe Pesci appears uncredited, as does Bob Dylan (as an eccentric artist). A shockingly frail Vincent Price appeared in Edward Scissorhands (1990) immediately after this, yet in Backtrack Price looks healthy and hearty, considering his age, though he may have shot his scenes as early as 1988. Julie Adams had an eye-opening part in The Last Movie but apparently bore no grudge against Hopper for her rather humiliating role in that fiasco. The performances are, notably, all over the map, some teetering toward self-parody (Pesci), others seemingly lost for lack of direction (Ward, Sheen). Dean Stockwell comes off best, underplaying among the mostly broadly-done gangsters.

Now part of the Lionsgate library, Backtrack gets a fine Blu-ray release from Kino. Both cuts of the film, presented in 1.78:1 widescreen (approximating the original 1.85:1 theatrical ratio) look pristine as well they should as the film received a perfunctory theatrical release at best. The cinematography (by Ed Lachman) leans heavily on bright locations and primary colors and the Blu-ray services this well. The English DTS-HD Master Audio (2.0 stereo surround) is reasonably good if unexceptional and optional English subtitles are provided on this Region “A” release.

Supplements include a trailer but, more intriguingly, also an audio commentary with filmmaker Alex Cox (who appears in the film uncredited as “D.H. Lawrence” and worked on the script without credit) and actress/co-writer Tod Davies. It delves deeply into the film’s complex production and release.

Despite its many flaws, Backtrack has a dogged likeability. Everything is off-kilter and it’s hard sometimes to distinguish its occasional clever artfulness from its frequent profound incompetence. Definitely a must-see for fans of the self-immolating cinema of actor-director Hopper.

- Stuart Galbraith IV